Winter has never been my favorite season. I do, however, have a better relationship with it now that I am involved in agriculture. The growing season gets busy and overwhelming, and winter encouraging me to rest, plan, and catch up on other parts of my life is good for me. I also do most of my presenting and organizing while the plants sleep. I value and believe in that work of outreach, teaching and sharing with others and am glad that NH winters give me the space for it.

But the cold pains me, the dark comes so early, and being cooped up like my chickens starts to frustrate me. I miss the green, the flowers, the sounds of critters calling to each other at night. So, I look forward to spring and appreciate signs reminding me it’s coming.

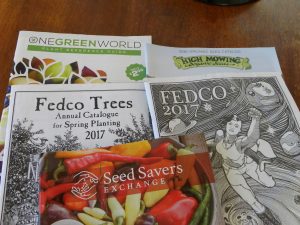

A Few of my Favorite Seed & Plant Catalogs

The arrival of seed catalogs starting in late December was the first. Right around the Solstice, when it is darkest but the light begins to grow, they appear. This prompts me to review my seed stock, look at our long range homestead plans and put together my orders. All gardeners love this task. My challenge every year is to be realistic and not over-order! How many trees can we really plant and tend to properly every year? I continue to research that question, and it does depend on the weather, but it’s often less than I convince myself of every January!

PV Solar Display – right side is most recent

The increasing light can also be tracked on our photovoltaic (PV) solar array display. This is our second winter with the system, and you can see the upwards trend of energy being made, with a few days off when snow covered the panels. Here in our forested area, we are entering the best season for making our own power. By February the sun angle and hours up has changed considerably since Winter Solstice, and with no leaves on the trees we generate lots of power. The panels also function more efficiently in colder weather.

Then, this week, seeds arrived!

Seed Packets from Seed Savers Exchange

This year I am excited about some of the heirloom varieties I found. After seeing the film “Seed: The Untold Story” – which I wrote about already for this blog – I decided to get more serious about saving my own seed, which means using fewer hybrid varieties. I won’t leave all of them behind – there are some great garden plants created by mainstream plant breeding (this is not genetic modification or engineering) which I’m grateful to have access to and that can eventually be stabilized into seed-savable plants. But there are also many old, stable varieties that I am thrilled to help continue the lines of.

Also, I had my eyes opened to the importance of New England Native American seeds by Dr. Fred Wiseman and the Seeds of Renewal Project. There are corn, squash and bean varieties that were developed over hundreds of years, selected for a level of hardiness that is unusual to find now and that we might really need as our weather becomes more unpredictable. Some of these varieties were the only to survive the Year Without a Summer in 1816. That kind of resilience is so valuable. (Dr. Wiseman will lead a workshop in Portsmouth NH on April 1, 2017.)

The Pile of Seeds Grows!

Abenaki Calais Flint Corn came from the northern Vermont Abenaki tribe and is known to have survived 1816’s year long winter. Calais is for drying and storing to make flour, cornmeal, and cereal. I am new to growing corn. The first farmer I worked for felt that corn used a lot of space and took a lot from the soil for not much nutrition. I still agree with that for sweet corn, but the dry corn options offer a winter food with more nutrients accessible after home processing.

I began exploring dried beans a few years ago and love them. This is a crop that fixes nitrogen in the soil and offers a high-protein, long shelf-life food and has very easy to save seed. I was at first daunted by processing by hand, but have not found that as hard as I’d feared. In fact, sitting by the fire, watching a movie or listening to music while I shell the beans is becoming a task I look forward to. Others like knitting, I like bean shelling. I am especially enamored with beans that climb. Using vertical space gives me more growing room, plus they dry well up off of the ground.

True Red Cranberry Pole Beans

Some great varieties I’ve already been growing include True Red Cranberry Pole and Jacob’s Cattle Bush, both on Slow Food’s Ark of Taste. True Red Cranberry is a northeastern Native American bean, big and beautiful, and I’ve had great luck with it the past two years. Jacob’s Cattle is said to be a Maine Passamaquoddy heirloom, big and tasty.

This year I found some new climbers to try. They aren’t quite as local. Hidatsa Shield Figure Beans, from the Hidatsa tribe of North Dakota, and Turkey Craw Beans, from the VA/NC/TN area are both on the Slow Food Ark of Taste. Good Mother Stallard Beans, named for Carrie Belle Stallard of Wise County, VA, can be traced back to the 1930s. Sarah Mostoller in PA found Mostoller Wild Goose Beans in 1865 in the crop of a wild goose and her family grew them for 116 years before donating them to Seed Savers. Those Turkey Craw Beans were also found in a bird – the craw of a turkey – by an 1800s hunter.

I might also track down some Sweeney Bush Beans, which is a Canadian heirloom possibly from the Mohawk, or Kanonsionni, people. It spent some generations being grown out by The Sweeneys of Nova Scotia and my mother was a Sweeney, so I feel a connection to it. I know that Dr. Wiseman has experience with this bean, so I hope to hear about it from him at his workshop in Portsmouth NH this April.

As a lover of stories, knowing the journey these seeds took before arriving in my mailbox delights me.

All this researching and dreaming keeps me connected to the gardens through the cold months.

In about a month I’ll take the next step: seed starting. Onions and leeks are first, in late February. To me, that’s really the start of gardening season. It will be here before we know it.

Winter in NH