“Nature is not a place to visit, it is home.” — Gary Snyder

To plant a tree is to be connected to a place with depth and longevity. When we were finally settled somewhere, “owners” of a place, it was a thrill to plant trees and bushes and other long lived perennials – anything beyond annual crops. We started with asparagus, rhubarb, berry bushes and trees. Fruit trees especially, plus a few for pollinators and medicine: peaches, pears, mulberries, linden, and unusual permaculture choices like persimmons and pawpaws.

This signified a level of stability and rootedness that I had been working towards for years. During all of that preparation I had studied how to plant and care for trees and other perennials. Now that it was time, though, having to do all of that and do it well was intimidating. I needed to sift through all the information I had garnered to figure out how best to keep them healthy and get a yield (permaculture principle 3).

Getting and preserving a yield

There are many pruning books, videos, and methods. Having read “The One-Straw Revolution” by Masanobu Fukuoka I knew that one could choose to be very hands off. Then again, permaculture orchardist Stefan Sobkowiak has an amazing organic orchard that he prunes and shapes intensively. There are also many variations in between. What should I do?

Feeling unsure of myself, and fearing hurting the trees, I started with minimal pruning. I saw the problems with that quickly with our peaches. We’d been warned that peaches could be difficult to grow in New England, especially organically. While I can confirm that it’s not easy to grow a perfect looking peach, our experience is that they grow fast, flower like crazy and make tons of delicious fruit! We still get hit by polar vortexes or super late frosts and lose a year like everyone else, but usually they thrive.

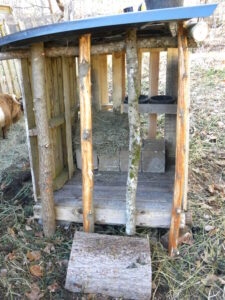

See the two big cuts we had to make after this overgrown peach broke?

The first peach we planted and barely managed ended up leaning sunwards, overloaded with fruit on long, high branches. Unsurprisingly, a main branch cracked and broke after just a few years. Luckily, it was above the graft so it has come back, but we lost a couple of harvests and I doubt it will live as long as it could have. So, I started pruning harder.

I also began to feel more confident in what I was doing and not second guess every single cut I made. I was able to visualize how the tree would respond to my cuts and what it would look like later on. The constant worry that I was doing it wrong faded. I could even enjoy spending time with the trees in the late winter cold, looking forward to their spring growth and summer fruit.

Pruning the Red Haven Peach in Winter

The Red Haven in Summer

I found a new level of satisfaction in the process when I read “Sprout Lands: Tending the Endless Gift of Trees” by William Bryant Logan a few years ago. In it, the author describes how most people lived in close, reciprocal relationship to the forests around them. They depended on and used their products for survival, intensively managing them with coppice and pollard techniques. Not only did these pruning techniques not

Pollarded Maple

kill the trees, but they made for longer lived individual trees, and healthier, more diverse woodlands. In Sproutlands he visits England, Spain, Japan, California and other places, finding the same story everywhere.

“I think having land and not ruining it is the most beautiful art that anybody could ever want.” -Andy Warhol

This is a narrative we recognize in permaculture. Rather than seeing humans and nature as two clashing entities, we recognize that humans are a part of the biosphere that evolved to have good, useful relationships with our fellow beings. That is how every species survives and thrives. So, I shouldn’t be surprised to once again have that reality shown to me, but given our species recent tendency to destroy things we depend on I find it hard sometimes to discern appropriate from destructive behavior.

When I first found permaculture this is part of what spoke to me. I was coming from both a farming and an activist perspective. As a farmer I appreciated permaculture’s practical improvements towards a sustainable, healthy food growing system. As an environmental and peace activist it was refreshing to find a way of looking at the world that did not assume that humans could only be problematic.

“The one who plants trees knowing that he or she will never sit in their shade, has at least started to understand the meaning of life.” – Rabindranath Tagore

This story of connection continues to this day. A 2022 study found that “the world’s healthiest, most biodiverse, and most resilient forests are located on protected Indigenous lands.” Even the World Bank with it’s poor track record of protecting land or people, recognizes that “Indigenous communities safeguard 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity and forests on their land are better maintained, with a higher preserved biodiversity than those on non-Indigenous lands.”

Now that I have gained skills and practice, and a larger understanding of what is possible, interacting and working with the plants brings me great joy. So does the abundant harvest that the trees and our work with them bestow upon us. It is my wish that all people have access to this level of interdependent security and resilience.

Unpruned Grapevines

Pruned Grapevines

Grapes to Harvest