Back in August I posted with an update on our season up until then. Now that 2023 is over I can give you a review of our full season as I take time in this quieter time of year to reflect.

A Great Butternut Year

I was moved to post about our season in August because of the challenges. I have written many summaries that cite drought as a limiting factor but this is the first one I’ve done where excessive rain is what caused us problems. That issue continued for the rest of the year. However, some of our fall crops were better than expected so our season did pick up towards the end.

To be consistent over time, I have kept most of the same topic headings as in previous years.

Weather & Water

This summer was the wettest on record for New Hampshire with 21 inches of rain recorded for June, July and August, 8 inches more than the average.

Given the recent droughts it’s hard to be annoyed by rain, but it definitely turned out there was such a thing as too much. We did not experience direct damage in our systems, like erosion, but the wet conditions still caused problems, the biggest one being plant diseases appearing and spreading more than usual.

Our water catchment systems came in handy in a different way than intended. Some of the storms had torrential rain that could have washed out paths and other areas. By emptying the storage totes in between storms we could keep the water in place and slowly drain it over a longer time period.

Our biggest crop loss actually had to do with the winter weather. The polar vortex in February destroyed our – and New England’s – entire peach crop. That was a big loss for us, as long-time readers will know I do a lot with peaches!

Rodents, Pests and Diseases

Basil – surprisingly undaunted by the wet conditions this year

As I mentioned, we did have more disease issues than usual this year. There was some sort of bacterial wilt that shortened the lifespan of a few of our crops: peas, cucumbers, and summer squash.

This year we took further measures to protect our plants from animals, especially porcupines and voles. First, for the porcupines, we added another run of fencing that includes a gate across the driveway that we close at night. It did not work at first because it turns out the porcupines can climb fences like a ladder. But with the addition of one string of electric along the top, we finally convinced them that our pear trees were not worth coming after. This also keeps out the deer, which weren’t a huge problem but sometimes did come through and nibble.

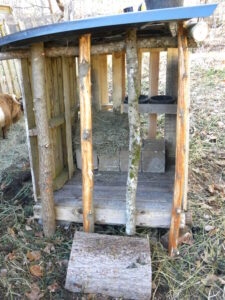

Vole Protected Root Crops

To deal with the voles we have started making garden beds that sit on metal mesh hardware cloth and have wooden sides. This uses more materials than my usual mound garden beds, but it is working. So, for the carrots and beets we plan to make more of these beds. We planted our potatoes in big plastic barrels cut in half. It did keep out the voles, but yields were very low. I had been worried about them drying out so positioned them in a somewhat shady area which was a mistake in such cloudy, wet weather. I also think they weren’t draining well enough since in a few of them the tubers just rotted. We’ll try again next year.

Gorgeous Spring Kale, Before the Caterpillars

The past two years we have had big outbreaks of caterpillars eating our brassicas. While I have always dealt with imported cabbageworm and cabbage looper, we suddenly have an overwhelming number of what I believe are cross-striped cabbageworms. These used to only be a problem in the South, but they have been making their way north with the changing climate. We are finding them far more destructive than other Brassica pests. Since we do not use any chemicals, we will look into barrier methods such as growing in hoop houses or under row cover.

Labor

The one upside to less productivity this year, was less physical work to do. Given that my arm injury was at its worst this year, it would have been a struggle to cut peaches for canning or keep up with much bigger yields.

It did give me more time to invest in some other important work in the world. We hosted more Seacoast Permaculture gatherings and classes and I became chair of the board for New Hampshire Peace Action which has been going through a transition in leadership, thus needing more volunteer help. To a large extent I came to farming and homesteading through being an activist, particularly a peace activist, in the tradition of The Nearings and others. So, to me, this is connected and complementary work anyway.

Animals: Bees

I continue to take a break from beekeeping while I try to heal my arm injury.

Diana and her triplets!

Animals: Goats & Pasture

Luna and her daughter, Diana, were this year’s mama goats.

The birthings went well, I’m relieved to say. However, Diana gave birth to triplets (which is a lot for a first time) and did not take to motherhood easily. There was about an hour when we thought she might entirely reject her kids – heartbreaking. But, we gave her support and coaching and she finally figured it out. That said, she was not an enthusiastic mother and did not give a lot of milk, so she will not be incorporated into the herd permanently. Luna, who is our star goat, had twin girls this year, and we will keep both of them. Hopefully at least one will be as great as their mom – healthy, vigorous, easy kidder, attentive mother and good milk producer. Making decisions like this is not easy for us, but we see careful breeding as our duty to the herd. (Note that

Luna with her kids, Maeve and Fionnuala, 5 months old

if you are buying goats or other working animals, I highly encourage you to buy from people who do cull and eat their animals, otherwise you are likely being sold their rejected stock.)

We are increasingly skilled at rotating the herd through our pastures, and the land is responding beautifully. Lots of lush green, very little bare ground, soil further coming to life and building up organic matter, carbon and nutrients. The positive power of well-managed grazing animals to improve land is amazing to witness!

Goats on Good Pasture

Our two new boy goats, Zac and Ike, who arrived Fall 2022 settled in well and Zac proved his ability to do his job – Diana’s triplets were his kids. Ike is the polled (born without horns) whethered (neutered) companion for Zac. I worried that an unhorned male would get pushed around a lot by our big horned boys, but he has tons of attitude and less threatening hormones so he appears to get his way more than anyone else!

Animals: Poultry

New Ducks

We incubated a couple rounds of chickens to raise for new young hens and meat. In the spring our two youngest female ducks disappeared, likely taken by aerial predators. A friend of ours who has good luck hatching ducklings helped us out with two rounds resulting in seven ducks. Only two were female but, well, better than none! Also our drake happened to die over the summer so we were able to replace him.

Grains

Despite last year’s promising test plots, our wheat failed this year. The fall planted crop didn’t overwinter well, and my attempts at spring planting may have been too late, or maybe birds and rodents ate the seed before I got there.

Red Sails Lettuce

Harvest totals 2023

Here is what we brought into the house and remembered to weigh. As you’ll see, some things had decreased yields, notably the cucumbers, summer squash, potatoes, kale & collards. There are a few things that I purposely planted less of, so if you compare years you would notice a decrease. These were intentional to better match what we need: garlic, radishes, snap beans. Our root numbers, especially beets and carrots are still low but should be recovering as we change our practices. At least this time I did not plant 10 times as much seed to get about the same number of carrots and beets.

On the other hand, check out our winter squash numbers! Also, dry beans and popcorn did extra well. Our small fruits had generally strong yields, too.

Alliums – garlic – 25.5 pounds (#) (155 heads); 150 garlic tops; leeks – 42.25#, perennial onions – 9.25#

Beans & Peas – snap beans – 50.75#; dry beans – 23.5#; sugar snap peas – 3.75#

Brassicas – broccoli – 8#; brussels sprouts – 9#; kale/collard – 12#

Calico Popcorn still on ears

Corn, popcorn – 10.5#

Cucumber – 39.5#

Eggplant – 14#

Melons – 7.5#

Greens – lettuce – 8.25#; nettles – 2#

Herbs – basil – 5#; dill – 1#

Mushrooms, winecap – 2#

Potatoes – 16.5#

Roots – beets – 11.75#; carrots – 30.75#; parsnips – 28.5#; radishes

Winter Squash Vines

– 58; turnips (gold ball) – 13.5#

Squash – summer – 25.25#; winter (butternut, long pie and Seminole) – 939.5#

Tomato – slicing – 29.75#; plum – 14.5#; cherry – 27#

Wheat – crop failed!

Fruit: azarole – 1#; blueberry – 6#; crabapples – 39.5#; currants, red & white – 2.5#; clove currants – 18.5#; elderberry – 3#; grapes – 13.5#; honeyberry – 2.25#; jostaberry – 5.5#; mulberry – 2.25#; raspberry – 2#; rhubarb – 17.5#

Maple syrup – 2.5 gallons

Sea salt – 1 gallon

We brought in 91 gallons of goat milk (from 4 goats); 28.5# goat meat; 3# goat lard

Our poultry harvest came to: 1,571 (130.9 dozen) chicken eggs from 12 hens; 480 (40 dozen) duck eggs from 3 ducks; chicken meat – 56#; duck meat – 6#

Gleaned/gathered off-farm crops: apples – 800#; blueberries we picked from Tuckaway Farm – 49#

Food Preserving

One of our Winter Squash Storage Shelves

Preserving food for the off-season is how we eat from our land year-round. Here’s a summary of what I put up from the harvest I just detailed:

Canned: applesauce – 20 pints; blueberries – 40 pints

Dried: kale/collards – 3 gallon bags; grapes (raisins) – 2 pts

Refrigerated: lactofermented cucumber pickles – 9 quarts

Frozen: blueberries – 2 gallon bags; grapes – 4 gallons; various berries – 6 gallons; snap beans – 12 pts; eggplant – 4 qts; summer squash – 6 qts; basil/garlic pesto – 13 pints; chevre cheese – 10 pints; mozzarella cheese – 12#; and most of the meat.

We also store these crops in a cold room or on the shelf: dried beans, popcorn, garlic, potatoes, carrots, beets, parsnips, turnips, winter squash, and apples.

Looking Ahead

My homestead plans for the coming year are to continue to refine our current systems to be more effective, easy to use, and in some cases more productive. A lot of the infrastructure work has been done here. I wouldn’t say this is our “lie in a hammock” time, but I do expect that we will continue to shift to even more harvesting with less big project work. That is the goal of permaculture… there is a lot of work up front to create the systems, and they will always need some attention, but the workload should not be as intense as we go along.

I’m going to try again with grain growing this year. And with any luck, I will have lots of peaches to can this time around!

Gorgeous Peach Tree… Hoping for Fruit in 2024